Category: biotech/medical – Page 2,467

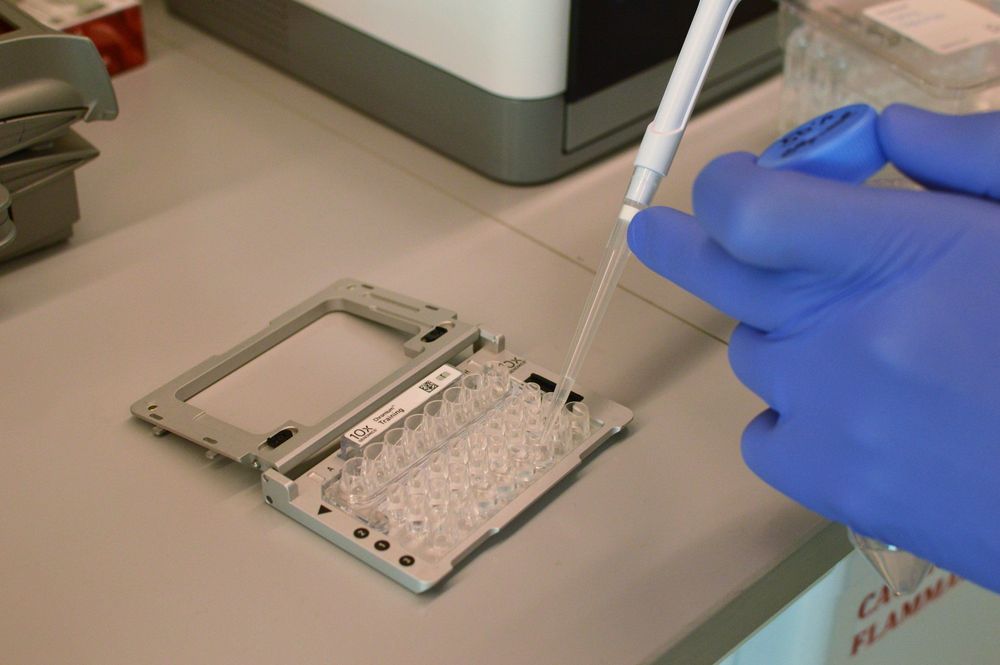

New techniques let scientists zero in on individual cells

NEW YORK (AP) — Did you hear what happened when Bill Gates walked into a bar? Everybody there immediately became millionaires — on average.

That joke about a very rich man is an old one among statisticians. So why did Peter Smibert use it to explain a revolution in biology?

Because it shows averages can be misleading. And Smibert, of the New York Genome Center, says that includes when scientists are trying to understand the basic unit of life, the cell.

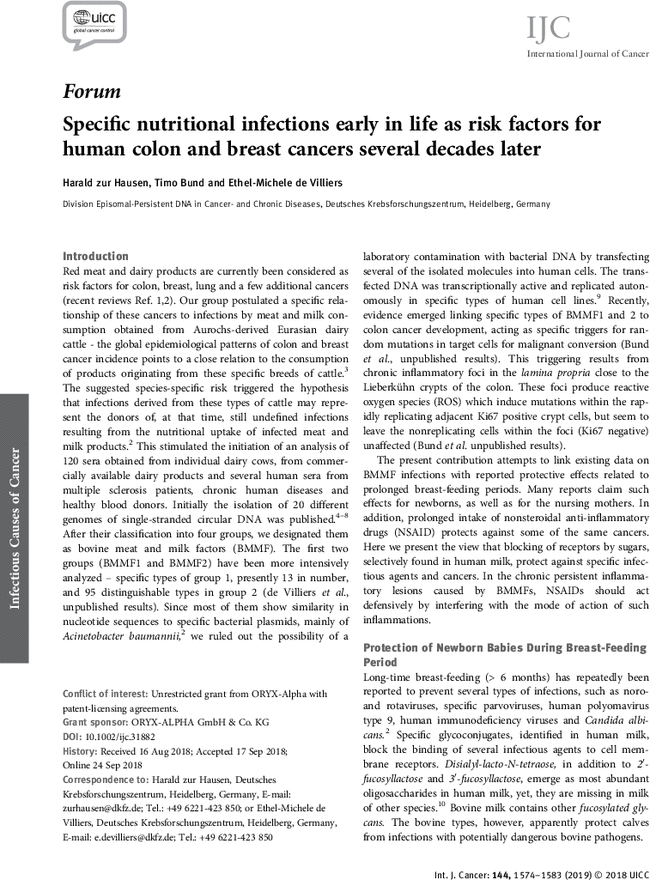

Specific nutritional infections early in life as risk factors for human colon and breast cancers several decades later

Infections with BMMF („Bovine Milk and Meat Factors ) in humans provide a clue, why the consumption of cow milk and meat correlates with colon and breast cancers.

E-mail address: [email protected]

Division episomal‐persistent DNA in cancer‐ and chronic diseases, deutsches krebsforschungszentrum, heidelberg, germany.

Correspondence to: Harald zur Hausen, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, Heidelberg, Germany, E‐mail:

Bacteria in frog skin may help fight fungal infections in humans

In the past few decades, a lethal disease has decimated populations of frogs and other amphibians worldwide, even driving some species to extinction. Yet other amphibians resisted the epidemic. Based on previous research, scientists at the INDICASAT AIP, Smithsonian and collaborating institutions knew that skin bacteria could be protecting the animals by producing fungi-fighting compounds. However, this time they decided to explore these as potential novel antifungal sources for the benefit of humans and amphibians.

“Amphibians inhabit humid places favoring the growth of fungi, coexisting with these and other microorganisms in their environment, some of which can be pathogenic,” said Smithsonian scientist Roberto Ibáñez, one of the authors of the study published in Scientific Reports. “As a result of evolution, amphibians are expected to possess chemical compounds that can inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria and fungi.”

The team first travelled to the Chiriquí highlands in Panama, where the chytrid fungus, responsible for the disease chytridiomycosis, has severely affected amphibian populations. They collected samples from seven frog species to find out what kind of skin bacteria they harbored.

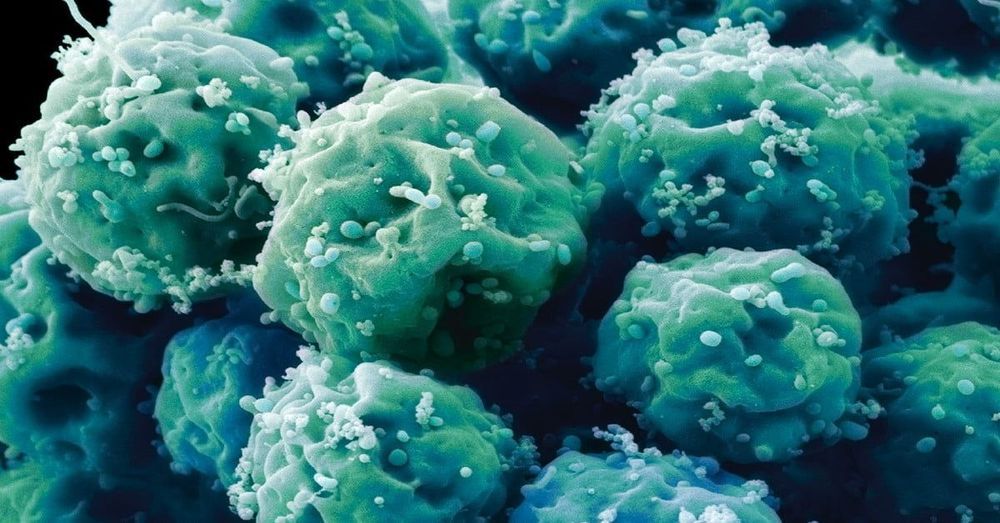

The good kind of fat

Metastasis is the leading cause of death from cancer, occurring when cancer cells separate from the original tumor to proliferate elsewhere. These new cancer cells travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Since these bodily systems are thoroughly connected, cancer can spread to a variety of locations. Breast cancer, for example, “tends to spread to the bones, liver, lungs, chest wall, and brain.”

Cancer cell plasticity — an ability that allows cancer cells to shift physiological characteristics dramatically — fosters metastasis and is responsible for cancer’s resistance to treatments. To combat its resistance, researchers at the University of Basel in Switzerland decided to turn cancer’s cellular plasticity against itself. They used Rosiglitazone, an anti-diabetic drug, along with MEK inhibitors in mice implanted with breast cancer cells. Their aim was to alter the cancer cells.

The drug combination hijacked the breast cancer cells during epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process by which the cells undergo biochemical changes. EMT plays a role in many bodily functions, such as tissue repair. In unaltered cancer cells, EMT allows them to migrate away from the original tumor while maintaining their oncogenic properties.

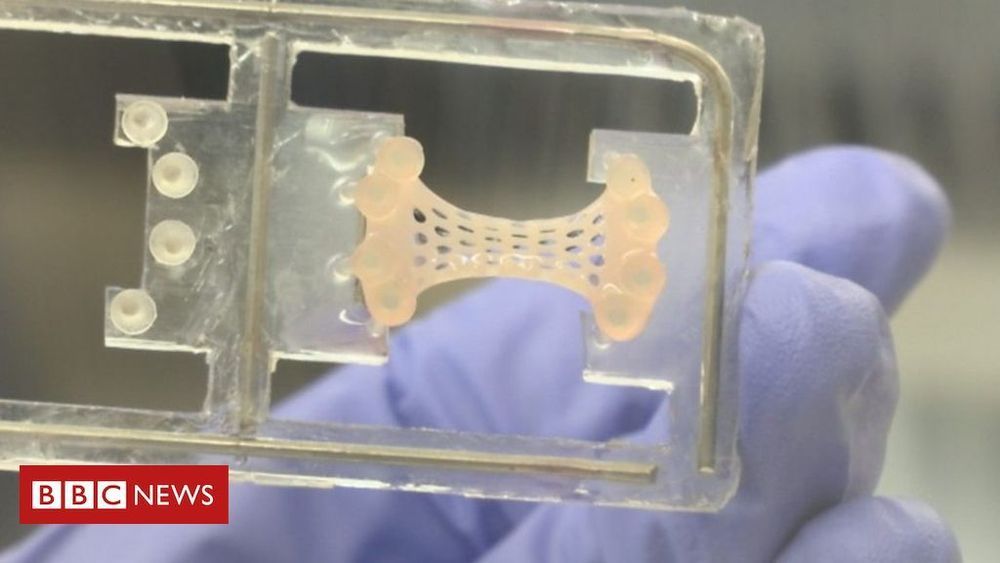

Stem cell heart patches ‘could save lives’

A medical breakthrough by scientists at Imperial College London could save thousands of heart patient’s lives.

Working with the British Heart Foundation, they have developed beating heart patches which could restore the muscle strength lost after a heart attack.

Claire-Marie Berouche has third-stage heart failure and she’s hoping the patch will change her quality of life.

Science has figured out how to freeze the aging process

Medical advances and living standards have extended the average human longevity from 48 years in 1955 to 71 years today, and the elderly are now the fastest growing segment of society. But while our life spans are improving, our health spans are not, writes science journalist Sue Armstrong in “Borrowed Time: The Science of How and Why We Age” (Bloomsbury), out now.

“Over the past 50 years, health care hasn’t slowed the aging process so much as it has slowed the dying process,” she writes, quoting gerontologist Eileen Crimmins.