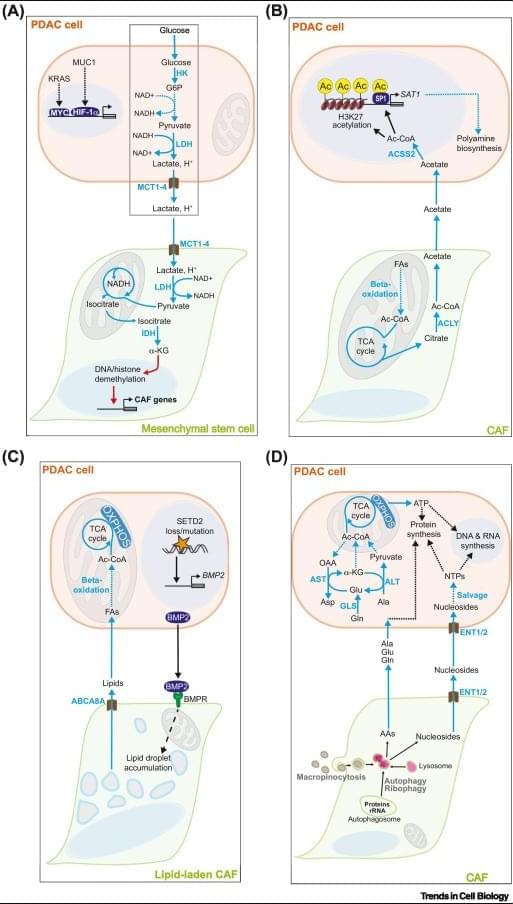

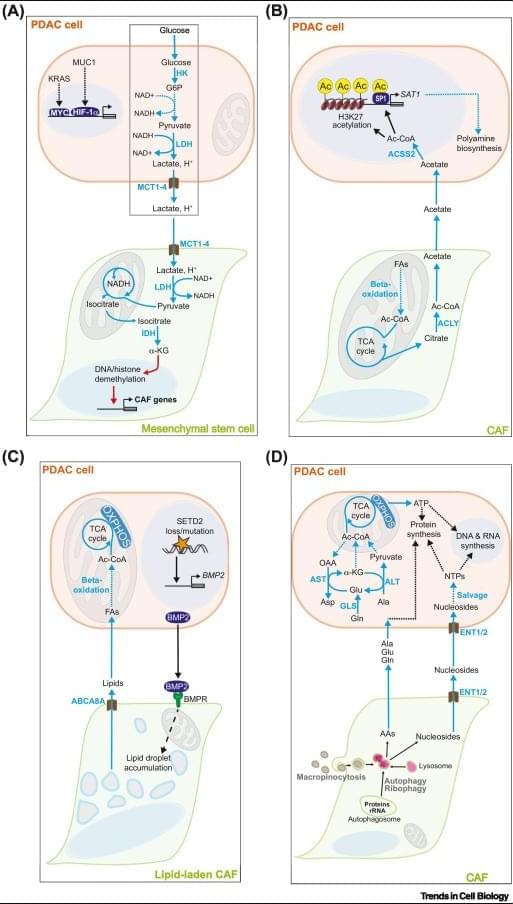

Metabolic crosstalk – the exchange of metabolites between cancer cells and non-malignant cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) – contributes to the aggressiveness of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) through a diverse array of mechanisms.

Under the selection pressure imposed by chemical stressors (acidosis, hypoxia) and scarcity of essential nutrients in the TME, PDAC cells establish mutually fitness-enhancing metabolic crosstalk pathways with cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor-associated macrophages, and other stromal cells.

PDAC cell metabolism inhibits the activity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells by outcompeting them for essential nutrients (glucose, amino acids, nucleosides, vitamins) and by flooding the TME with immunosuppressive metabolites (lactate, kynurenine, adenosine, and others).

Critical nodes of tumorigenic metabolic crosstalk pathways (enzymes and cell membrane transporters) are readily druggable and likely non-essential for healthy tissues. https://sciencemission.com/Tumor%E2%80%93stromal-metabolic-crosstalk-in-PC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is an aggressive malignancy with a dire prognosis. Standard-of-care chemotherapy regimens offer marginal survival benefit and carry risk of severe toxicity, while immunotherapy approaches have uniformly failed in clinical trials. Extensive desmoplasia in the PDAC tumor microenvironment (TME) disrupts blood flow to and from the tumor, thereby creating a nutrient-depleted, hypoxic, and acidic milieu that suppresses the function of antitumor immune cells and imparts chemotherapy resistance. Additionally, recent seminal studies have demonstrated crucial roles for metabolic crosstalk – the exchange of metabolites between PDAC cells and stromal cell populations in the TME – in establishing and maintaining core malignant behaviors of PDAC: tumor growth, metastasis, immune evasion, and therapy resistance.

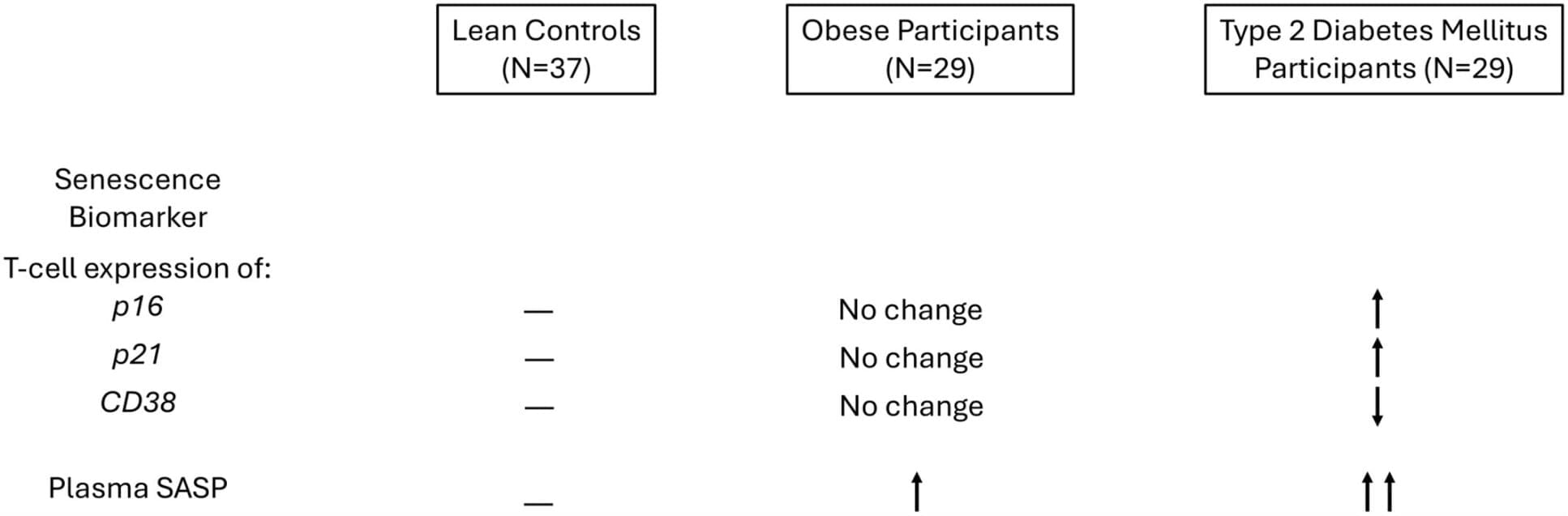

Anti-Aging Drug Combo Extends Mouse Lifespan by 35%. Human Trials May Be Next

Anti-Aging Drug Combo Extends Mouse Lifespan by 35%. Human Trials May Be Next