The molecular synthesizer once thought to be impossible to make is now quite a possibility due to this discovery with electron beams that can heal crystalline structures and also build objects from electron beams this could one day be amplified to create even food with light into matter electron beams. Also this could create even life or even rebirth a universe or planet or sun really eventually anything that is matter. Really it is a molecular assembler with nearly limitless applications.

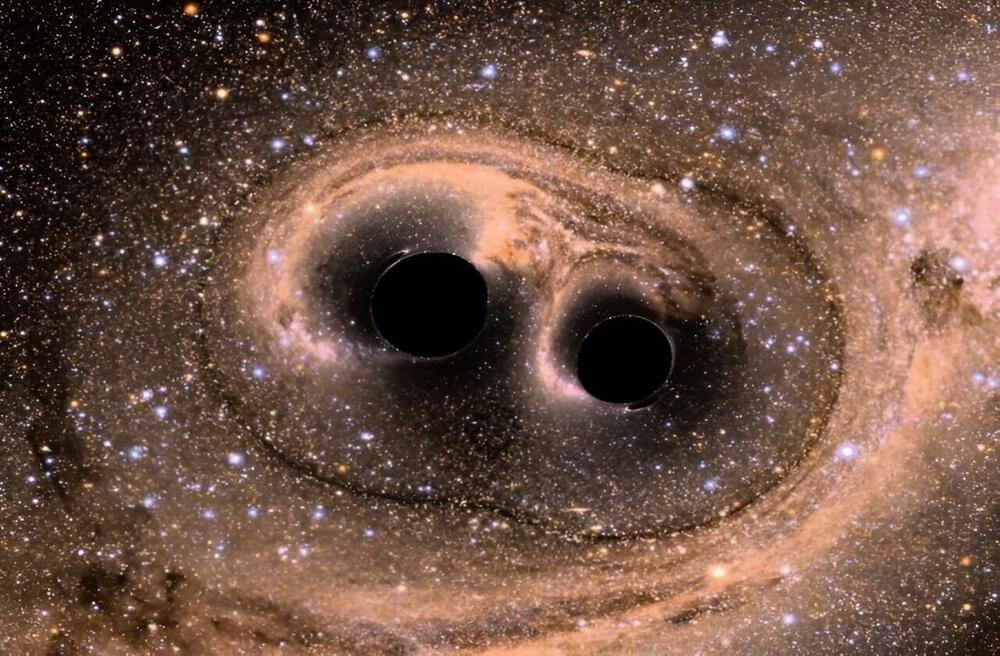

Electron beams can be used to heal nano-fractures in crystals instead of causing further damage to them, as initially expected by researchers who now report their surprise findings. Used to power microscopes that examine the smallest materials in the universe, electron beams may also be able to be used to create novel microstructures one atom at a time.

A feat once thought impossible, researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities (UMN) behind the discovery said it had been assumed that using electron beams to study nanostructures carried the additional risk of exacerbating microscopic cracks and flaws already in the material.

“For a long time, researchers studying nanostructures were thinking that when we put the crystals under electron beam radiation to study them that they would degrade,” explained Andre Mkhoyan, a UMN chemical engineering and materials science professor and the lead researcher in the study.