For Bob Dylan, the feel of a particular genre—be it country, rock, or blues—served to inspire his ideas that were searching for expression beyond boundaries. It was the recklessness and volatility of rock that allowed him to express the grudging anthem of “Like a Rolling Stone,” and it was the country medium that enabled “Lay Lady Lay.” The boundaries of a specific genre would have restricted the reach of Dylan’s songwriting. Arguably, Dylan writes and performs his best work precisely because he is able to transcend the constraints of particular musical styles. Dylan, then, is a prime example of a “Renaissance mind,” but the phenomenon is general: music has genres, but the musicians themselves may be most creative when they explore the full realm of possibilities within their reach.

Similarly, the borders between scientific fields and disciplines are not natural boundaries; really, there are no boundaries. Disciplines, fields, and subfields are just one way of clustering knowledge and methodology on increasingly fine-grained levels, but this clustering is not unique, and there is not even an obvious optimality criterion for the clusters. Many boundaries may simply reflect the way in which a field developed historically. Working within the confines of a field may help us to structure insights and ideas, but—similar to a musician’s fixation on a certain genre—the boundaries can impede our creativity and restrain our advances into certain directions. During our most creative night science moments, when we come up with potential solutions for problems and dream up hypotheses, when we need to make new and unexpected connections, we are better off if our mind is free to transcend the fields and disciplines. After all, if there were no boxes, we would not have to think outside of them. This kind of thinking may also be called horizontal [7] or lateral thinking [8].

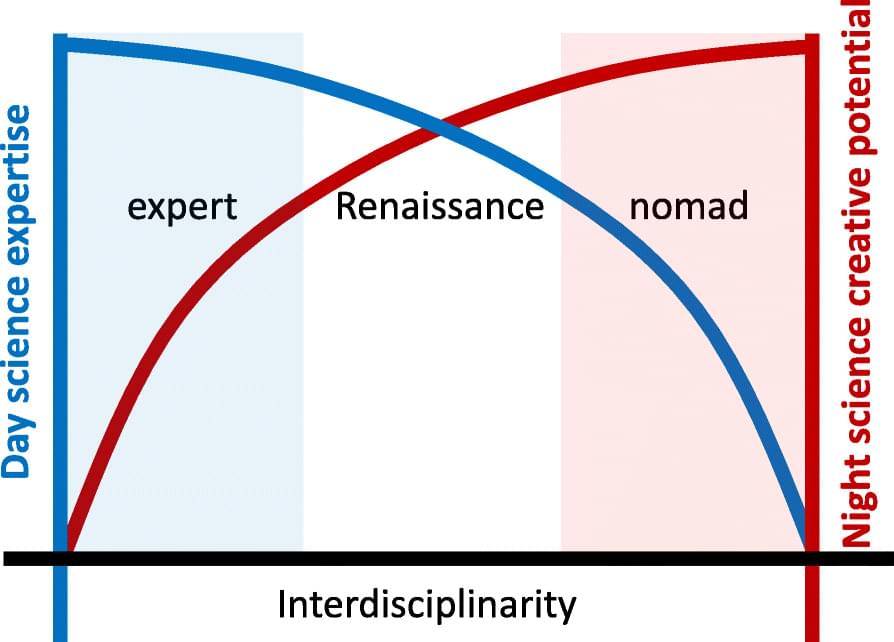

To transgress the boundaries of a field, it is highly useful to have an understanding of multiple disciplines, either as a person or as a team, as this provides more opportunities to make connections. In the modern practice of science, the interdisciplinary aspect is often interpreted as a collaboration between scientists that work side by side in different disciplines. But true interdisciplinarity—even in a collaborative framework—requires us to think across fields. At some point, someone on the team will need to have that idea, and that someone will likely be the one with access to multiple fields. Thus, while the framework of science is disciplinary, a scientist’s creativity benefits from interdisciplinarity. This may explain why so many eminent biologists were originally educated in a different field: just think of Max Delbrück, Mary-Claire King, or Francis Crick. But there is also an important role for large and diverse teams: if more varied ways of thinking, more diverse ideas come together at the water fountain, they provide a fertile ground for making connections across borders—the modern workplace replacement of the traditional café, where creative people have traditionally met to exchange ideas [9].