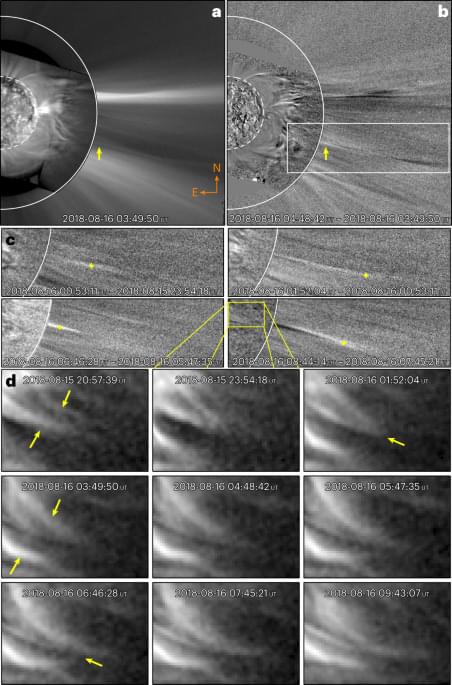

Thus, our SUVI observations captured direct imprints and dynamics of this S-web in the middle corona. For instance, consider the wind streams presented in Fig. 1. Those outflows emerge when a pair of middle-coronal structures approach each other. By comparing the timing of these outflows in Supplementary Video 5, we found that the middle-coronal structures interact at the cusp of the southwest pseudostreamer. Similarly, wind streams in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 emerge from the cusps of the HCS. Models suggest that streamer and pseudostreamer cusps are sites of persistent reconnection30,31. The observed interaction and continual rearrangement of the coronal web features at these cusps are consistent with persistent reconnection, as predicted by S-web models. Although reconnection at streamer cusps in the middle corona has been inferred in other observational studies32,33 and modelled in three dimensions30,31, the observations presented here represent imaging signatures of coronal web dynamics and their direct and persistent effects. Our observations suggest that the coronal web is a direct manifestation of the full breadth of S-web in the middle corona. The S-web reconnection dynamics modulate and drive the structure of slow solar wind through prevalent reconnection9,18.

A volume render of log Q highlights the boundaries of individual flux domains projected into the image plane, revealing the existence of substantial magnetic complexity within the CH–AR system (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Video 7). The ecliptic view of the 3D volume render of log Q with the CH–AR system at the west limb does closely reproduce elongated magnetic topological structures associated with the observed coronal web, confined to northern and southern bright (pseudo-)streamers (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Video 8). The synthetic EUV emission from the inner to middle corona and the white-light emission in the extended corona (Fig. 3c) are in general agreement with structures that we observed with the SUVI–LASCO combination (Fig. 1a). Moreover, radial velocity sliced at 3 R ☉ over the large-scale HCS crossing and the pseudostreamer arcs in the MHD model also quantitatively agree with the observed speeds of wind streams emerging from those topological features (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 6 and Supplementary Information). Thus, the observationally driven MHD model provides credence to our interpretation of the existence of the complex coronal web whose dynamics correlate to the release of wind streams.

The long lifetime of the system allowed us to probe the region from a different viewpoint using the Sun-orbiting STEREO-A, which was roughly in quadrature with respect to the Sun–Earth line during the SUVI campaign (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 6). By combining data from Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory-Ahead’s (STEREO-A) extreme ultraviolet imager (EUVI)34, outer visible-light coronagraph (COR-2) and the inner visible-light heliospheric imager (HI-1)35, we found imprints of the complex coronal web over the CH–AR system extending into the heliosphere. Figure 4a and the associated Supplementary Video 9 demonstrate the close resemblance between highly structured slow solar wind streams escaping into the heliosphere and the S-web-driven wind streams that we observed with the SUVI and LASCO combination. Due to the lack of an extended field of view, the EUVI did not directly image the coronal web that we observed with SUVI, demonstrating that the SUVI extended field-of-view observations provide a crucial missing link between middle-coronal S-web dynamics and the highly structured slow solar wind observations.